[Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the August 2000 issue of Grassroots Motorsports. Some information and prices may have changed. All text has been left as it originally appeared in print.]

Synthesizing, coordinating, orchestrating: However you describe the process, it is the proper use and coordination of cockpit controls which make a race car circulate quickly around the track. …

Steering

A pretty straightforward gadget, the steering wheel. However, many race drivers either address the wheel improperly, turn it in too early, discontinue using it prematurely, or fail to return it to where they found it once they are done using it.

Okay, having glossed over the improper use of the steering wheel, I can see that I might need to elaborate somewhat on the correct use of this device.

Addressing the wheel improperly: Most race drivers know to position their hands in the proper three o’clock and nine o’clock position the steering wheel. However, improper arm bend is what I was alluding to when I mentioned “addressing the wheel improperly.” Formula cars require a relatively straight-arm approach because of their tiny steering wheels and quick-ratio steering racks. However, in sedans, many drivers do not allow enough arm bend (90 to 120 degrees in the elbow) to allow for the occasional 120-degree correction required to catch an oversteer slide or to facilitate a progressive tum-in rate.

Turning in too early: Many drivers turn in too early from the outside edge of the track to the apex of the corner. The result of hitting an apex too early is usually excessive understeer at the outside of the comer, just prior to your track-out point.

Tome, early apexing is a mental discipline or self-confidence issue. Your subconscious mind may be screaming, “We’re going too fast! Tum in, you fool!” If you are confident in your ability to catch the occasional oversteer and if you are carrying the correct speed into the corner, your best response to your subconscious is, “Bite me. This is a late-apex comer, you wuss.”

Discontinue using the wheel prematurely: In street driving, a linear or constant tum-in rate of the steering wheel will do just fine. However, in many late-apex, off-camber or decreasing-radius corners, you will need a progressive turn-in rate. It works like this: first you need to tum in gradually to get the suspension and tire contact patches to accept the initial turn in; next, you need to increase the turn-in rate slightly once the chassis is set.

Failure to return the steering wheel where you found it: Dad’s advice was right: After the job is done, put the tools back where you found them. Your race car chassis is happiest when its steering wheel is in the three and nine position. Put it back.

You started your tum into the corner with your hands in the three and nine position. As you exit the corner onto the straightaway, the steering wheel should be returned to the three and nine position. If you have to finesse the steering wheel out slightly to use the whole track, do so, but work towards a slip angle or drift that naturally returns the steering wheel to center. You should end up with your front wheels parallel to the straightaway at the corner’s exit.

Momentum is important. Excessive understeer or oversteer can kill momentum. Use every bit of the race track available to maintain your momentum. If you have any doubt as to how this technique works, watch the video of the Formula Vee race at the SCCA national championships. These guys are the masters of maintaining momentum.

Braking

Braking follows steering because braking is an integral part of getting your race car turned into the comer properly. Braking and steering are inseparable.

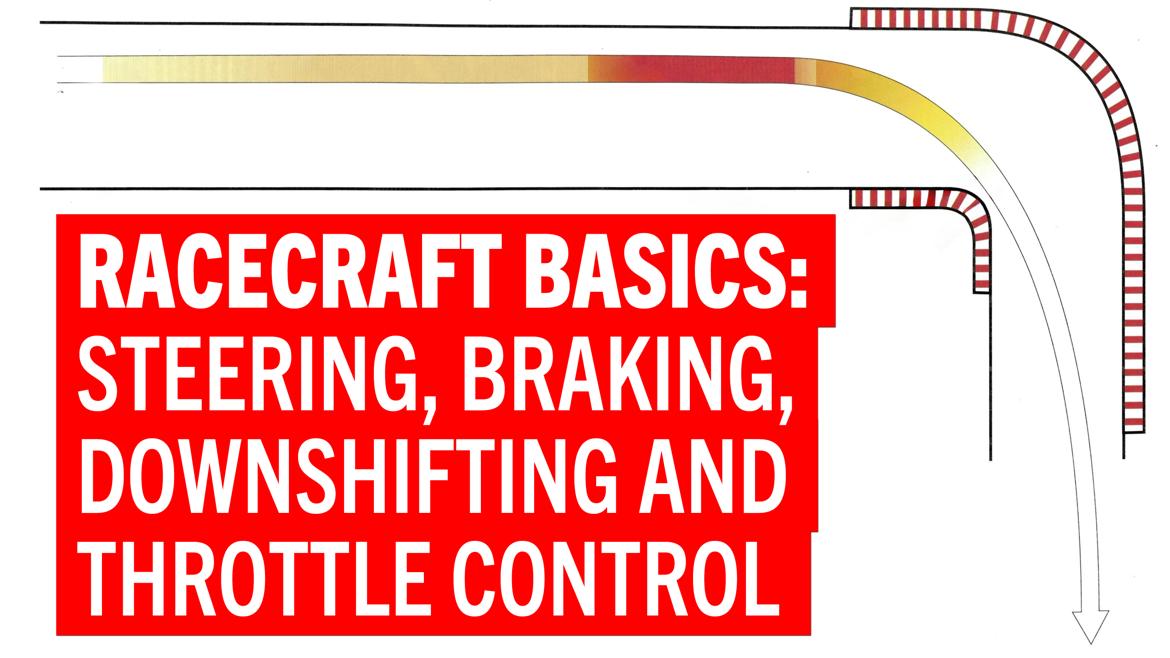

Looking at our illustration on page 64, you can see that we have divided the braking zone into four parts. However, in reality, braking, downshifting and trail braking should all flow together smoothly. For illustrative purposes, the steps are as follows: first is the Straight Line Braking Zone; next is the Brake and Downshift Zone; then comes the Heavier Braking Zone; and finally, your Trail Braking Zone.

From the Straight Line Braking Zone all the way to the apex, we have color-coded the brake pressure required for entry into a typical 90-degree corner. The length of the Straight Line Braking Zones will vary with the type of race car, its entry speed, the size of its brakes, the tires and the car’s weight. Our illustration will work for most street stock sports cars coming off a moderate-length straightaway.

The yellow zone indicates that we are easing on the brakes to transfer weight forward to get the front suspension to compress and the front tire contact patches to expand prior to entry of the corner. Also, we must steady the car for brake and downshift.

The Brake and Downshift Zone: In the orange zone, we are slowing the car even more and we are going to do our braking and downshifting prior to the corner.

Heavier Braking: The red zone, still a straight line, indicates slightly heavier braking after our gear exchanges are done as we slow the car and prepare for turning into the corner.

Next is the Trail Brake Zone, marked first in orange as we trail off the brakes and begin our turn into the corner. Finally, we fade to yellow as we gradually ease off the brakes, close on the apex and get ready to transition to throttle (shown in white).

Ideally, our straight line braking, brake and downshifting, and trail braking will be a flawlessly smooth process so that we can optimize momentum while simultaneously transferring weight smoothly to the front tires to prepare for turning into the corner. While the steering wheel will mandate when and how quickly we will turn into the corner, the car’s suspension and front tire contact patches must be ready to accept the steering input.

Trail Braking, where we gradually release the brakes as we turn into the corner, insures that we have kept enough weight on the front end to keep the suspension compressed and tire contact patch area optimized on the track.

Without the brakes working in harmony with the steering, we will not have the proper turn-in grip and we will probably understeer as we exit the corner. Finesse. Smoothness. Momentum. Think like the chassis; become the chassis; don’t anger the chassis.

Throttle

After trail braking comes the throttle. Like our smooth braking transitions, we also need smooth throttle transitions as we exit the corner. Premature acceleration or a heavy right foot will negate everything we have done to achieve balance and maintain momentum through the corner. An early throttle application will transfer weight off the front wheels and put us into an understeer condition. Understeer kills momentum, and winning races is all about maintaining momentum.

Okay, let’s say we goofed and carried a little too much speed into the corner in our Trail Braking Zone. We know this because the rear end of our car has just stepped out, and the small orifice in our posterior has started to pucker. Not to worry, because we have prepared for this eventuality.

Remember the steering section and the 90- to 120-degree bend we put in our elbows? Oh yeah, so we are ready to catch that treacherous oversteer! And the throttle? Now the throttle is our best friend. Since we haven’t nailed the gas pedal to the floor, we have loads of available throttle to use; therefore we have loads of weight we can transfer to our car’s loose rear wheels. We simply turn the steering wheel into the direction of the slide, catch the oversteer and apply the throttle smoothly. Bada bing, bada bang, bada boom.

Incidentally, I wish I had told you about the dead pedal a might earlier. We could certainly use the deal pedal about now to help feel what is going on with the back of the car. Well, please read on, maybe we can use the dead pedal next time we get in this bind.

Dead Pedal

The dead pedal (or rest pedal) is that immovable pedal mounted just behind the left front fender well area, just to the left of the clutch pedal. While it goes largely unnoticed by the average street driver, it can be very ergonomically beneficial to the racer.

For example, a firm push on the dead pedal with one’s left foot before the race car steps out can help relieve severe sphincter constriction. The dead pedal accomplishes this by firmly planting one’s butt tightly into the seat back, thereby providing better feedback (via the rear suspension, through the chassis and up through the seat) as to where the race car’s rear end is at the moment.

It is amazing how a benign device like the dead pedal can help disseminate the g force loads that can stress your body during the course of a long race. Even if you have a formfitting Butler seat and a six-point harness, the dead pedal is an ergonomic tool which will help you stave off fatigue during long drives.

Shifting

Heel-and-toe downshifting is perhaps the hardest thing for a new race driver to learn. This is because to do it properly you must accomplish several motions: a) brake in a straight line with the ball of your right foot on the brake pedal; b) push down the clutch pedal with your left foot; c) rev the engine with the outside of your right foot (while the ball of your foot is still on the brake pedal giving constant pedal pressure); d) downshift from a higher gear to the next lower gear; e) release the clutch to engage the next lower gear; and f) repeat the process if you have yet another gear to downshift before the end of the Straight Line Braking Zone.

Without professional supervision, heel-and-toe downshifting is one of the hardest things to master because you are simultaneously using the brake, clutch, gas pedal, shift lever and monitoring the engine speed on the tachometer. For the mastery of this technique alone, it is worth going to a high-performance driving school. Truly fast race drivers can match revs on downshifts smoothly and late brake with supreme confidence.

If you cannot afford to go to a professional racing school, you may have an experienced racer friend who can teach you braking and downshifting techniques. However, do not expect him or her to offer their car for the lesson. It is likely that your instructor will expect you to strip your own gears and thrash your own synchro rings.

If you have no other viable alternative, you may refer to our braking illustration for brake and downshift instructions. By placing step-by-step brake and downshift instructions (and foot position illustrations) next to the Straight Line Braking Zone, you may be able to comprehend just how the Braking and Heel/ Toe Downshifting sequence develops.

Here are few tips and diagnostic points to determine whether you are doing your braking and downshifting correctly. We suggest you practice them at an accredited driving school or at your local autocross clinic.

a. Before starting to practice shifting, place your car in neutral and practice revving your engine with the outside of your right foot while simultaneously applying brake pedal pressure with the ball of your right foot. Be sure you have mastered this before you move on.

b. Practice in an appropriate area with qualified supervision. (P.S. Again: Since this author and GRM have already suggested that you attend an accredited performance driving school to learn from a professional instructor, we hold ourselves harmless from damage, injury or death that may be caused by anyone who chooses to practice these techniques in any place or venue where qualified, professional performance driving instructors are not supervising and riding with yoµ in a safe car.)

c. When downshifting from a higher to a lower gear, you must maintain revs of approximately 1000 rpm more than the gear you are downshifting from. For example, if you are shifting from third to second and traveling at 3000 rpm, the engine must be revved up to 4000 rpm to match revs when the clutch is released in the lower gear. If the tires chirp when the clutch is released, this indicates that you have not revved the engine up sufficiently.

d. A smooth clutch pedal release and constant brake pedal pressure are vital to a smooth brake-and-downshifting technique.

e. All braking and downshifting must be done in a straight line prior to the corner. This insures that the rear end of the car is in line with the front end of the car; hence, if you “under-rev” on the downshift and lock up the tires directly connected to the drivetrain, the car is not as likely to spin out due to oversteer. Remember: The downshift is not complete until the clutch is released; thus the clutch must be released before the corner, not in it. Start slowly and work your way up.

f. When trail braking, or gradually releasing the brake as you enter the corner, look far ahead to the apex and beyond so that your mind will tell your right foot just how much to release the brake pedal. Use brake, turn in, apex and track out marking points to establish consistency.

g. When accelerating out of a corner, be sure your car’s nose is pointed where you want it to go before squeezing on the throttle. Line up the apex, track out and straightaway reference points before you go to the throttle.

Putting All of Your Lessons Together

Coordinating brakes, steering, shifting and acceleration skills is important in achieving smooth, consistent, quick lap times; however, these skills are only part of the equation.

Without the ability to look far down the track or ahead to the apex of an upcoming decreasing-radius corner, one is not a complete race driver. Without the ability to plan passing strategies far in advance or without a highly-developed sense of peripheral vision, you will not be ready to compete successfully with experienced professionals on track.

Steering, braking, downshifting and accelerating skills are best practiced on an autocross or performance driving school track until they become automatic. Once you never miss a brake point, never miss a downshift, never miss an apex and never blow a corner exit, then you can begin to concentrate on more adranced skills which will ultimately make you a smooth, fast and consistent driver who is ready to race on the track with experts.

Many aspiring race drivers are in a hurry to get on the race track and test their driving talents against other drivers. All too often these new drivers neglect the important basic race driving skills in favor of pouring money into their race car for short-term results. When this is not successful, these inexperienced drivers simply spend more money on their cars for more short-term results. This cycle can be never ending.

The better solution is to begin first to perfect one’s driving skills and then to move up the racing ladder. Solid race driving skills last forever, while a $10,000 racing engine has a very limited shelf life. There is a reason why drivers like Rick Mears, Michael Andretti and Al Unser Jr. attended professional road racing schools before they stepped into a formula car.

Aim high, but begin modestly. Buy a car you can afford to campaign, to abuse or even to lose. Spend the rest of your money for professional race chiving instruction. Professional race driving instruction is the single motorsport investment which will benefit you from your first race until you hang up your Nomex many years down the road.

Tim Sharp has driven for several factory teams in amateur and professional competition, including Volkswagen, Ralt, Porsche, Autodynamics, TRD USA and TOMs/Toyota. He has also instructed for the Bob Bondurant and Skip Barber racing schools and is currently planning on building a car for NASA’s new Factory Five Challenge Series.